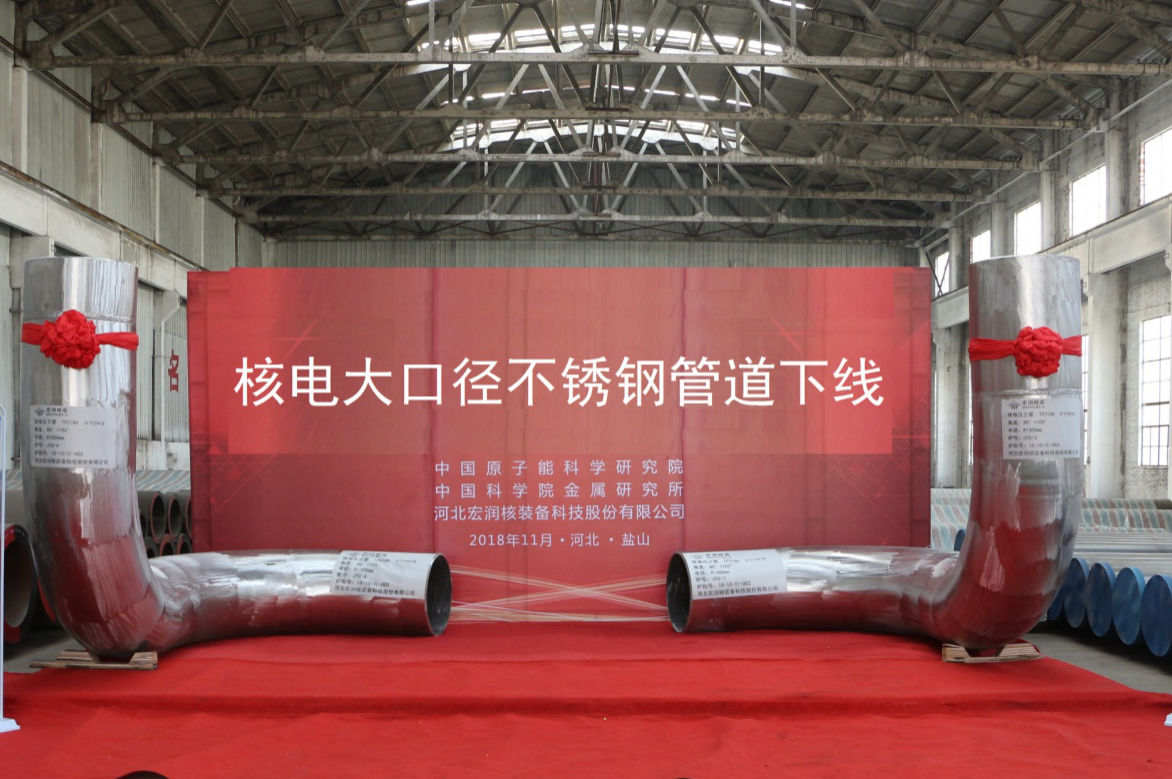

Équipement nucléaire

Nuclear Equipment continues to move towards "extreme manufacturing"and has embarked on a path of self-development and innovative development that is unique and independent.

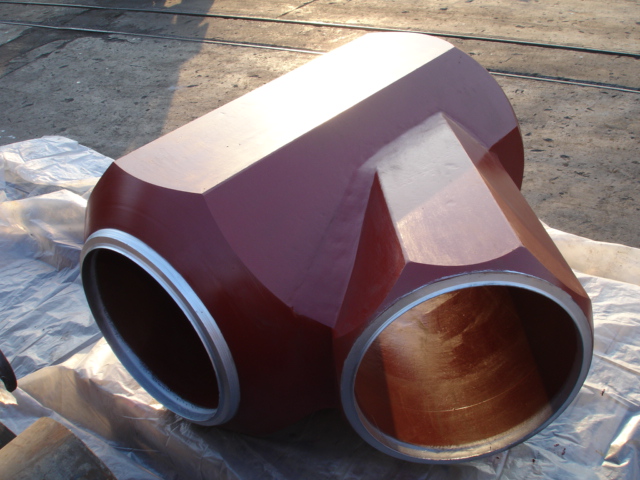

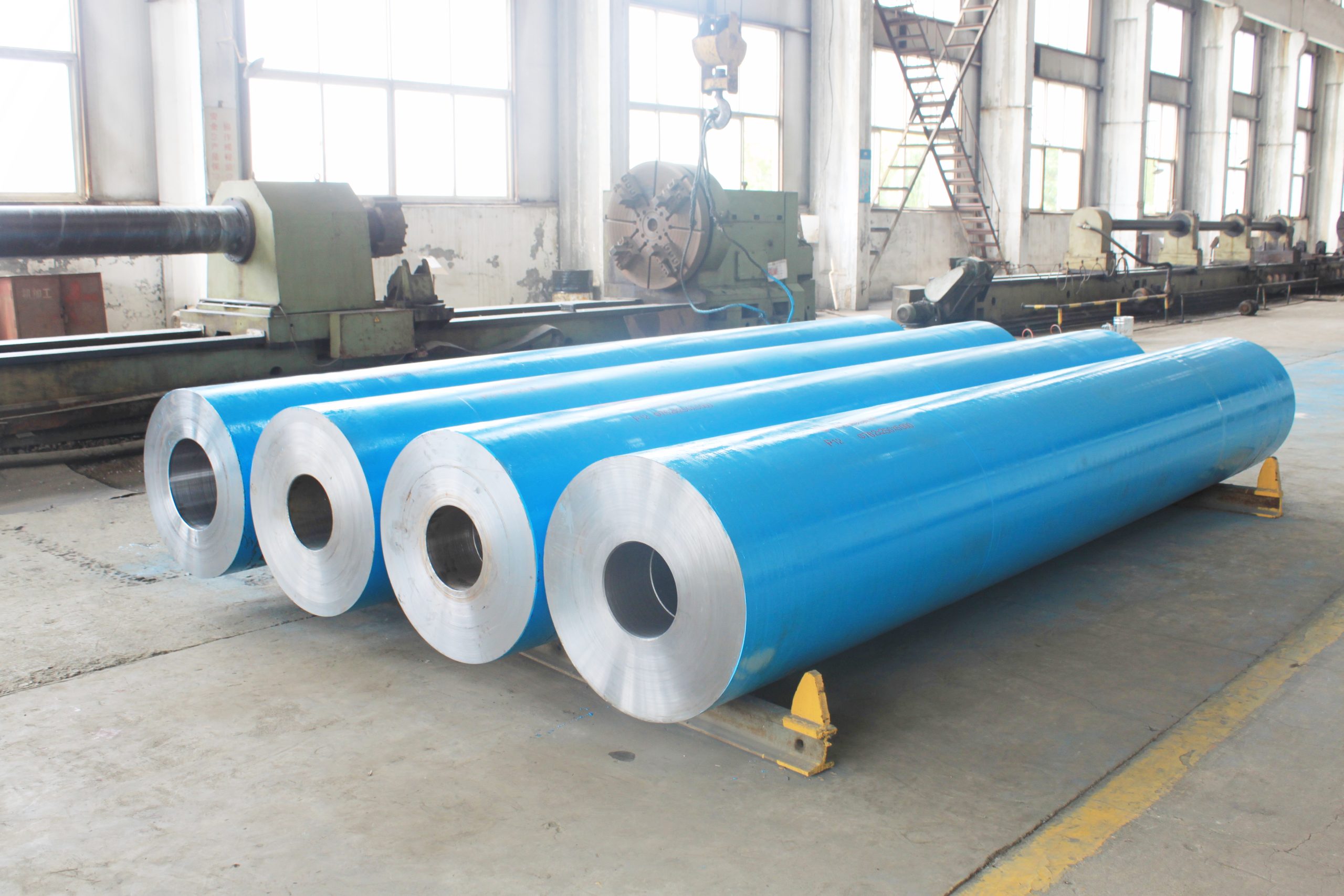

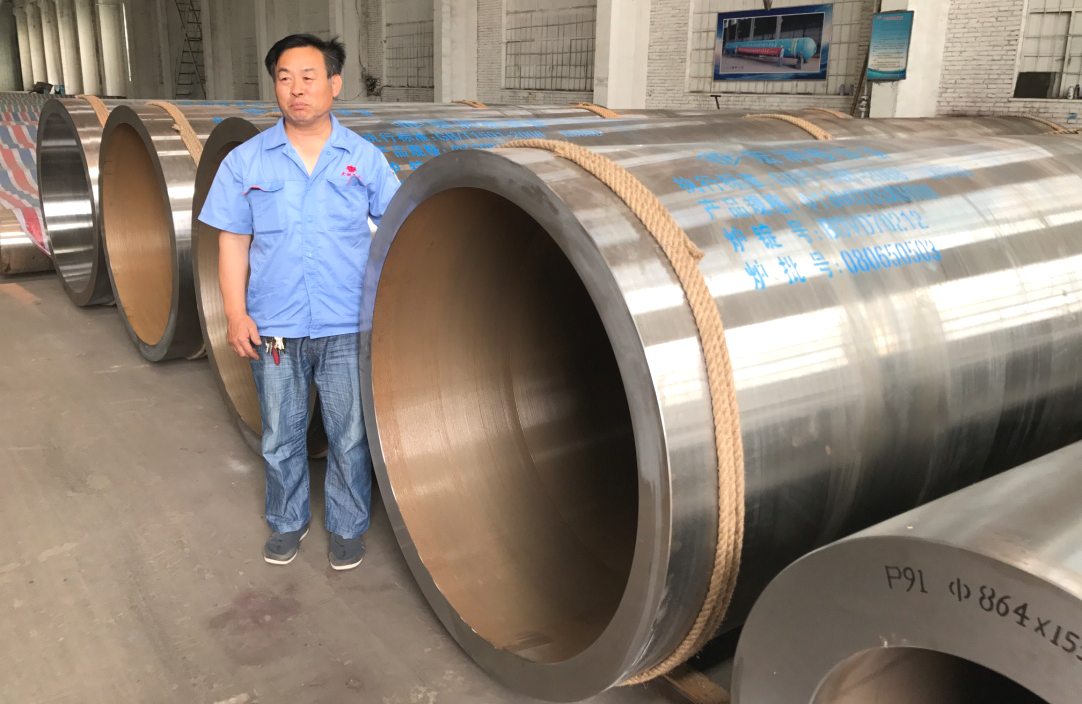

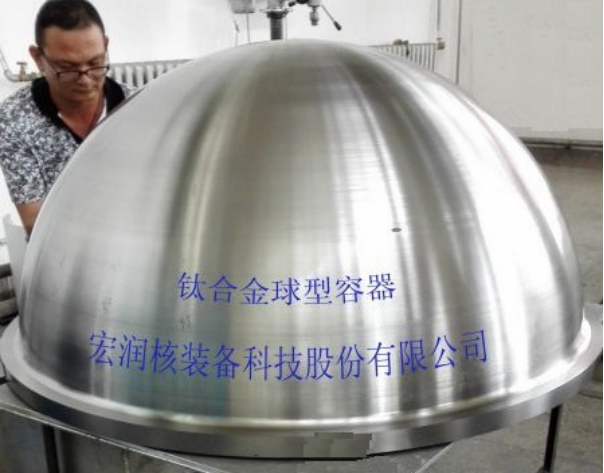

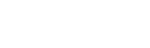

Nuclear Equipment is carrying out strategic cooperation and research and development with state-owned enterprises and research institutes such as China First Heavy Industries,China Second Heavy Industries,China Nuclear Power Academy,Metal Research Institute of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Baosteel Special Steel,taking the 50000 ton vertical extrusion unit independently developed and manufactured as the platform,actively undertaking national major projects and special projects,vigorously developing high-end products such as nuclear grade l steel pipes,nuclear main pipes,nuclear main pump shells, CAP1400 nuclear power super pipes,titanium alloy pipes,large marine diesel engine crankshafts,primary pressure pipes,reactor pressure vessel near net shaped hot extrusion components,extrusion valve doors, and G115 high-end steel pipes,nuclear main pump shells,S90 crank-shafts and other new products. The main standard and material include TP316L, TP316H; SA335 P11, P22,P91,P92, etc.; SA-508Gr3.C1.1; P280GH and other nuclear grade steel pipes and fittings.

The concept of "Force" in the nuclear industry is often misunderstood as a static property, a number on a datasheet. But when we look at the strategic ecosystem formed by Nuclear Equipment in collaboration with titans like China First Heavy Industries, Baosteel Special Steel, and the Metal Research Institute of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, we see that strength is actually a dynamic result of a complex metallurgical journey. This isn't just a manufacturing story; it’s an exploration of how we manipulate the very lattice structure of matter to withstand the most unforgiving environments on Earth.

At the heart of this entire technological movement is the 50,000-ton vertical extrusion unit. To understand our products, one must first understand the physics of this platform. Most industrial components are forged or rolled, processes that often leave behind "seams" or inconsistent grain structures. But when you subject a billet of TP316L or SA-508Gr3.C1.1 to 50,000 tons of vertical pressure, you are effectively forcing the metal to flow in a fluid-like state through a precision die. C'est "near-net-shaped" extrusion à chaud. It’s a process that preserves the integrity of the metal’s "fiber" or grain flow, ensuring that the finished nuclear main pipe or CAP1400 super pipe has no weak points, no weld-seams in the primary structure, and a level of homogeneity that was previously thought impossible at these scales.

When we talk about the CAP1400 nuclear power super pipes, we aren't just talking about large tubes. We are talking about the primary arteries of a Generation III+ reactor. These pipes must manage the immense thermal hydraulic stresses of a pressurized water reactor. By using vertical extrusion, we eliminate the need for longitudinal welds. In the world of nuclear safety, every centimeter of a weld is a centimeter that requires ultrasonic testing and a centimeter that could potentially harbor a stress corrosion crack over a sixty-year lifecycle. By providing a seamless, extruded solution in materials like TP316H or the P91/P92 high-strength ferritic steels, we are essentially removing the "vulnerability points" from the reactor's primary coolant loop. This is where the partnership with the China Nuclear Power Academy becomes vital—it ensures that our R&D isn't just happening in a vacuum, but is strictly aligned with the safety margins and operational demands of the next century of carbon-free energy.

The material science here is deep. Take G115, Par exemple. This is a high-end martensitic heat-resistant steel designed for temperatures that would make standard stainless steel lose its structural "memory." Moving G115 through a 50,000-ton press requires an intimate understanding of the material's TTT (Time-Temperature-Transformation) Diagramme. If the temperature drops too quickly during extrusion, the martensitic structure becomes brittle; if it stays too high, the grain size grows uncontrollably, ruining the toughness. Our collaboration with the Chinese Academy of Sciences allows us to model these phase transformations in real-time. We are essentially "tuning" the steel as it is being shaped. This results in products like our nuclear main pump shells and primary pressure pipes that possess a rare combination of high yield strength and high fracture toughness.

Then there is the marine dimension—the S90 crankshafts and large marine diesel engine components. A crankshaft in a massive vessel is subjected to immense torsional fatigue. Traditional manufacturing involves machining away massive amounts of material from a forged block, which often cuts through the grain flow of the metal. Our approach uses the power of the extrusion platform to ensure the grain lines follow the contour of the crank, much like the rings of a tree follow its growth. This creates a part that is naturally resistant to the initiation of fatigue cracks. Whether it is a titanium alloy pipe for high-corrosion environments or a P280GH fitting for a steam system, the philosophy remains the same: the manufacturing process must respect the physics of the material.

The inclusion of SA335 P11, P22, and P92 in our portfolio represents a commitment to the entire energy spectrum. These are the workhorses of high-pressure piping. But even a "Norme" material becomes something extraordinary when processed through a 50,000-ton vertical unit. The precision of the wall thickness, the concentricity of the pipe, and the smoothness of the internal surface—critical for reducing turbulence and erosion-corrosion—are all superior to traditional piercing and rolling methods. We are not just making components; we are engineering the reliability of the national grid.

When a client integrates our extrusion valve doors or our reactor pressure vessel near-net-shaped components into their project, they are benefiting from a localized, high-tech supply chain that spans from raw ore to final precision-machined part. We are standing on the shoulders of giants—the researchers at China Second Heavy Industries and the metallurgists at Baosteel Special Steel—to deliver a product that is "born" under pressure and "bred" for endurance. This is the new standard of nuclear equipment manufacturing: where the sheer force of 50,000 tons meets the microscopic precision of advanced material science. We invite you to explore a partnership where the integrity of the metal is as unyielding as our commitment to safety and innovation.

.png)